Travelers’ Texts

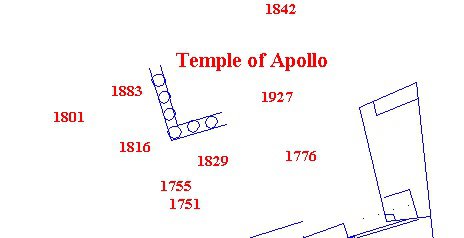

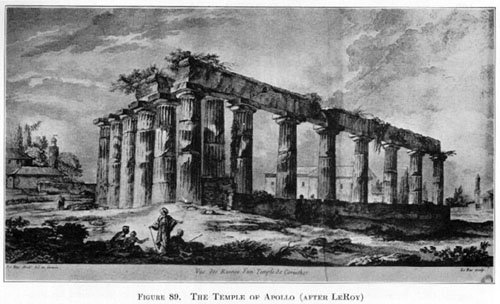

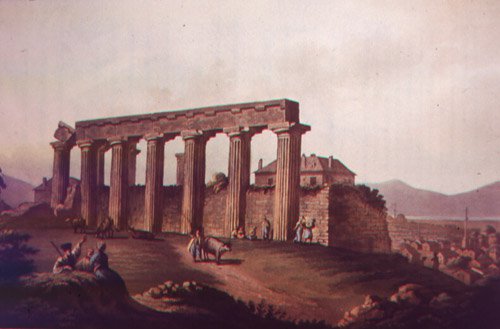

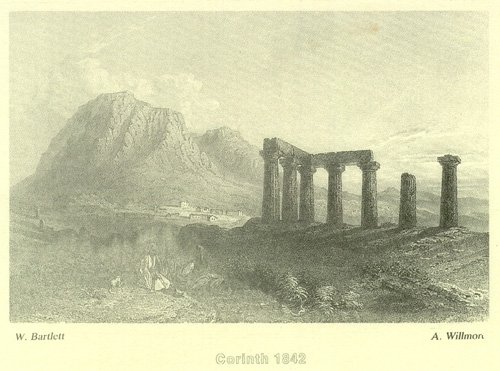

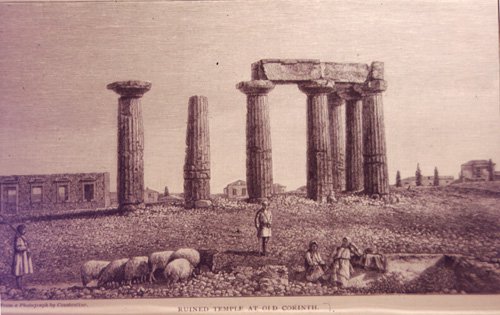

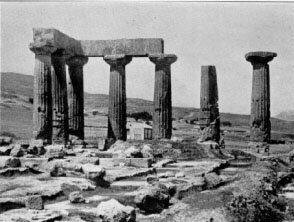

Nearly every traveler who visited Corinth mentions the temple, and the majority of the illustrations that survive are also of the temple. Three issues come up in the different descriptions: the identification of the temple, the reason for the destruction of four columns between 1776 and 1800, and the rediscovery of the columns after the War of Independence. The question of the temple’s identification is the most popular one for comment: 16 of the travelers either suggest a deity or discuss the variety of suggestions of others. Up to 1848, the suggestions vary wildly. Three suggest Octavia (one of which also suggests Juno), three Neptune (one of which also suggests Venus), two Juno (one of which also suggests Octavia) and three discuss the multiplicity of suggestions. After 1848, 5 of the seven travelers suggest Minerva Chalinitis. Interestingly, only one traveler, Keppel, suggested an identification with the Temple of Apollo, which is the current candidate and has been since its excavation at the turn of the century.

Three travelers comment on the destruction of the 4 columns. Clarke (1800) and Fuller (1818) both suggest that the owner destroyed the columns because he wanted to use the material for his building project, and Clarke names the owner as the Governor. Turner (1813) believes that the Turk wanted merely to make room for his addition. It is hard to know which explanation was the truth, and in fact, it might have been both.

The travellers who visit Corinth as it is being rebuilt after the War of Independence (1821-1829) describe the temple as if it had been buried with debris. In 1829, Keppel writes that five were found when the debris was cleared from that area. However, Trant, who also travelled in 1829, describes all seven. Fitzmaurice, who travelled in 1832, describes only three columns found. Estourmel, also travelling in 1832, notes that seven columns were found by soldiers. While everyone but Trant described the columns as having been “found” that seems possible, but as there is not complete accord between the four of them, and the number of columns found varies in a way that doesn’t make sense, it is hard to know exactly what was to be seen at this time. However, as this is the only abberation in terms of number of columns reported other than Leroy, it seems clear that something was making the counting of the columns difficult.

Dreux 1665-1669

“Mais les Romains brulerent tellement cette belle ville quand ils las prirent qu’il n’y reste plus que quelques colonnes, qui sont les restes d’un ancien palais, et une ancienne porte de la ville…”

But the Romans burned this beautiful city so much when they took it that there are only a few columns left, which are the remains of an old palace, and an old city gate... (158)

Spon 1675-1676

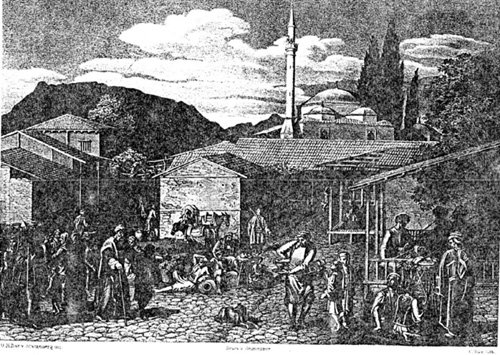

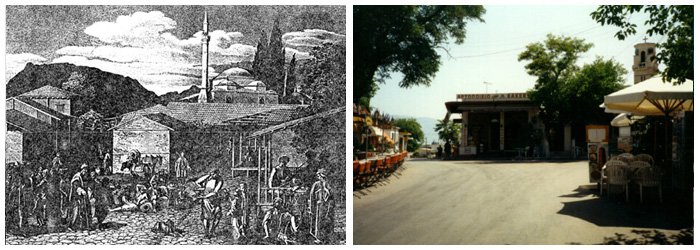

“Nous sumes saluer Panagioti Cavallarie marchand Athenien, qui fait presque toujours la sa residence. Son frere demeure aussi au bazar et nous vimes chez luy une inscription Latine de Faustine femme de l’Empereur Antonin. Nous allames voir une douzaine de colonnes, qui paroissent de loin sur une eminence, un peu plus haute que le Bazar, a la maison du Vayvode. C’est le reste de quelque Temple des Payens. Ces colonnes me parurent le plus antiques qu’aucunes qu j’eusse jamais vues a cause de leur extraordinaire proportion. Car bien qu’elles soient d’Ordre Dorique, elles n’ont point la meme proportion que les autres qui se trouvent a Athenes, et ailleurs…(discusses measurements) Du reste elles sont semblables a celles d’Athenes etant canelees et sans base. Les architraves qui restent encore dessus sont de grandes pierres de 12 pieds de long.”

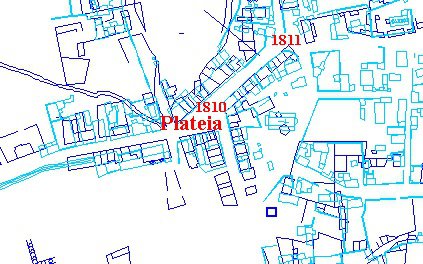

We came to greet Panagioti Cavallarie Athenian merchant, who almost always makes it his residence. His brother also lives in the bazaar and we saw at his house a Latin inscription of Faustina, wife of the Emperor Antoninus. We went to see a dozen columns, which appeared from a distance on an eminence, a little higher than the Bazaar, at the house of the Vayvode. It is the remains of some Temple of the Pagans. These columns seemed to me the most ancient than any I had ever seen, because of their extraordinary proportion. Because although they are of Doric Order, they do not have the same proportion as the others which are in Athens, and elsewhere... (discussed measurements) Moreover they are similar to those of Athens being fluted and without base . The architraves that still remain on it are large stones 12 feet long. (296-7)

Wheler 1676

“Some distance Westwards of this, (the house in which he found some inscriptions), and upon a Ground somewhat higher than the Bazar, we went to see eleven Pillars standing upright. They were of a Dorick Order, channeled like those about the Temple of Minerva, and Theseus at Athens: the matter of which Pillars we found to be ordinary hard Stone, not Marble: But their Proportion extraordinary; for they are eighteen foot about, which makes six foot Diameter, and not above twenty foot and an half high; the cylinder being twenty, an the Capitals two and an half…There is a Pillar standing within these, which has the same Diameter: but is much taller than the others, although it hath part broken off, and neither Capital nor Architrave, remaining near it: so that of what Order it was, is yet uncertain. The others are placed so with their architraves, that they shew, they made a Portico about the Cella of the Temple: And the single Pillar is placed so towards the Western-end within, as shews it supported the Roof of the Pronaos.” (440)

Pococke 1736-1740

“At the southwest corner of the town are 12 fluted doric pillars about five feet in diameter and very short in proportion…” (describes and compares with Parthenon, 7 pillars are to the west and 5 to the south, one pillar without a cap is near them) (174)

Chandler 1765

“The chief remains are at the southwest corner of the town and above the bazaar or market, 11 columns supporting their architraves, of the doric order, fluted, and wanting in height near half the common proportion to the diamter. Within them, toward the western end, is one taller, though not entire, which it is likely, contributed to sustain the roof.” (240)

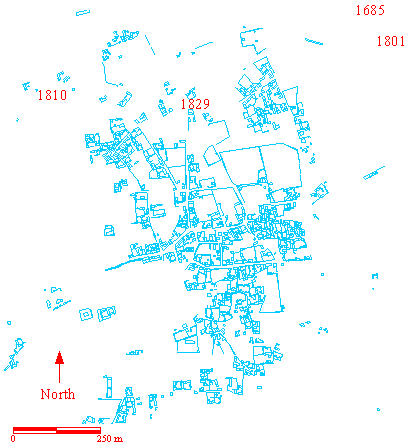

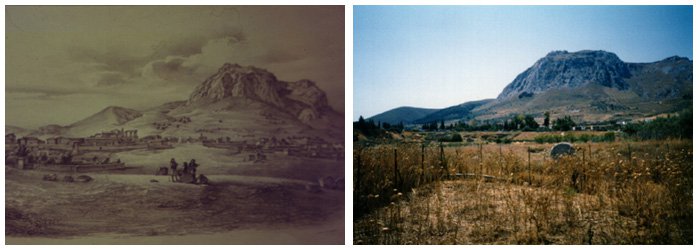

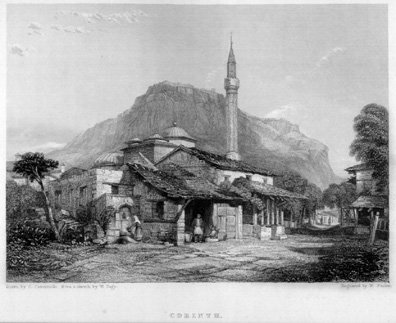

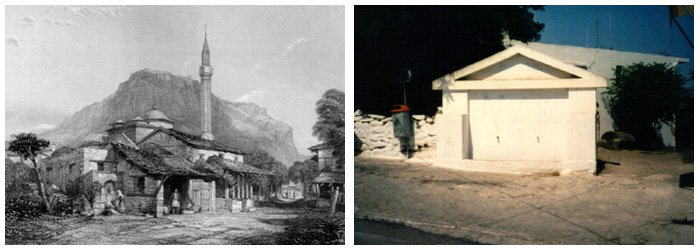

Dodwell 1801-1806 (figure 5)

“...But at present seven only are standing, which rest on one step.” (191)

Clarke 1800-1803

“In going from the area of this building towards the magnificent remains of a Temple now standing above the bazar whence perhaps the doric pillar already mentioned may have been removed, we found the ruins of antient buildings; particularly of one partly hewn in the rock opposite to the said temple. The outside of this exhibits the marks of clamps for sustaining slabs of marble once used in covering the walls, a manner of building perhaps, not of earlier date than the time of the Romans…” “In this building were several chambers all hewn in the rock, and one of them has still an oblong window remaining. We then visited the temple.” (remarks that Wheler found 11 but now there are only 7) (550-551)

“We found only seven remaining upright: but the fluted shaft before mentioned may originally have belonged to this building, the stone being alike in both; that is to say, common limestone, not marble, and the dimensions are, perhaps, exactly the same in both instances, if each column should be measured at its base.” (552)

“The destruction that has taken place, of four columns out of the eleven seen by Wheler and Chandler, has been accomplished by the governor, who used them in building a house; first smashing them into fragments with gunpowder.” (552)

He identifies the temple as that of Octavia. “...This temple occupied the same situation with respect to the agora that the present ruin does with regard to the Bazar; and it is well-known that however the prosperity of cities may rise or fall, the position of the public mart for buying and selling usually remains the same.” (555)

Hughes 1813

We “strolled through the town which contains little to remind the traveller of Corinthian splendour, except a few columns of some temple, which antiquarians find very difficult to identify: their antiquity is attested by their massive structure…” (241)

Turner 1813

“Corinth contains within its walls no remains of antiquity, but some small masses of ruined walls, and seven columns, with part of the frieze, of a Temple, of which some columns were pulled down to make room for a miserable Turkish house, to which it joins. These columns are about 60 feet high and 10 in circumference. They are supposed by some travellers (among whom, Dr. Leake) to be the ruins of the temple of Juno.” (292)

Bramsen 1813-1814

“...the antiquities of the place, which include, among many other objects worthy of attention, the remains of the temple of Juno, those of the temple of Octavia and the singular dripping fountain of the nymph Pirene…” (55)

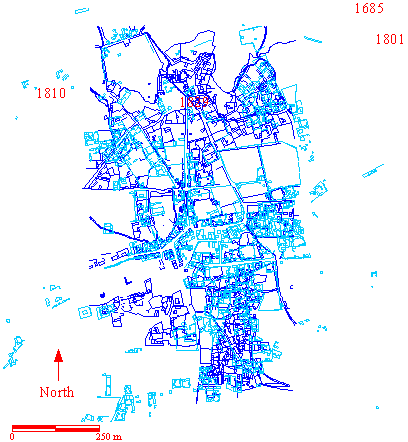

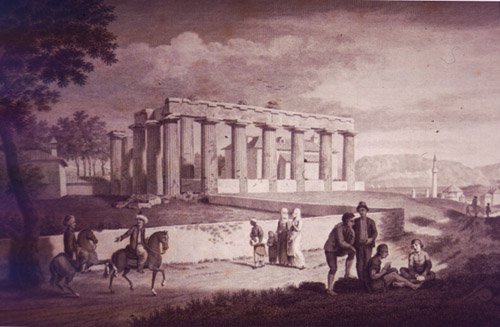

Williams 1816 (figure 6)

Identification of temple unknown: Juno, Venus, Neptune? Chandler says Sisypheum mentioned by Strabo. Proportions are like the Neptune temple at Paestum. (393-394)

Woods 1816-1818

The temple “...figured in Stuart, the first building we saw of Grecian times. In his days eleven columns were still standing. Now there are only six, but is yet a magnificent ruin…” (228)

Fuller 1818-1820

“They [the columns] are of porous stone and were originally encrusted with a red cement, some traces of which still remain. When Chandler visited Corinth, and even down to a much later period, eleven of them were still standing, but the Turkish proprietor took down four the employ the materials in the rebuilding of his house.” (33)

Keppel 1829-1830

“A Cephaloniote has been commissioned by the government to erect some public buildings and the governors’ house is in progress. Near the site of this building, the workmen employed in clearing away the rubbish have discovered five Doric columns, belonging, I believe, to a temple dedicated to Apollo.” (11)

Trant 1829-1830

“In the town are seven columns of a Doric temple supposed to have been dedicated either to Venus or Neptune; they bear the marks of great antiquity and are singular, as the shafts are formed of but one piece.” (313)

Fitzmaurice 1832

“Of the ancient remains of Corinth there is nothing but the front of a Temple with three columns; certainly a poor specimin of its former architecture.” (69)

Estourmel 1832

“...Quelques soldats errent au milieu de ses debris, en cherchant a piller, et dans cette solitude, qui semble maudite, sept colonnes (Chandler eu trouver douze) d’ordre dorique, demeurees debout et qu’on croit avoir apartenu au Temple de Neptune, temoignent seules que, dans un autre temps, il fut des Dieux pour Corinthe…”

...some soldiers wander in the midst of its debris, seeking to pillage, and in this solitude, which seems accursed, seven columns (Chandler found twelve) of the Doric order, which remain standing and which are believed to have belonged to the Temple of Neptune, alone testify that, in another time, there were gods for Corinth... (86)

Burgess 1834

“There exist but seven columns of a Temple or portico…the entablature resting upon five of them, one (marked 6) [he gives a schematic drawing of the locations] wants a capital, there are vestiges of tryglyphs.” (166)

Author chooses to identify temple as the Portico of Octavia and therefore the temple is Augustan in his view. (166)

Quin 1834

“The celebrated ancient columns, each formed of one block of stone, which every traveller has noticed, are in Corinth, with the exception of the Acrocorinthus, the only objects worth attention in the way of 'lionizing.’” (213)

Temple 1834

“Opposite the governor’s house are the remains of a Doric Temple…” (60)

Addison 1835

“Over these [shattered remains of Turkish mosques], in front, were seen the seven majestic Doric columns of the ancient temple and behind the lofty acropolis…” (16)

Stephens 1835

“...Seven columns of the old temple are still standing, fluted and of the Doric order…” (49)

Giffard 1836

“A Temple situated in the upper part of the town has given rise to much discussion as to the date of its erection and the deity to which it was dedicated.” (102)

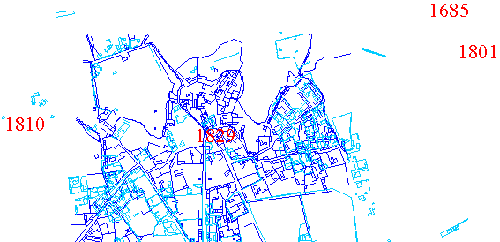

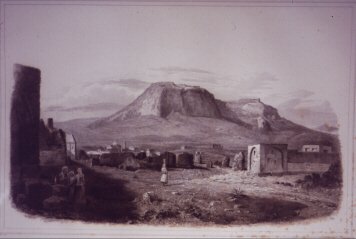

Blouet 1839 (figure 7)

“...Sur le point le plus eleve de ville, se retrouvent les ruines d’un temple: cinq colonnes de la facade posterieure resent encore debout, ainsi que deux de la partie laterale; presque toutes sont surmontees de l’architrave; elles sont en pierre calcaire et etaient couvertes d’un stuc qui les revet encore en plusiers endroits…Stuart, qui a donne une description desrestes de ce temple avait trouve quatorze colonnes debout lors de son voyage.”

...on the highest point of the city, there are the ruins of a temple: five columns of the rear facade are still standing, as well as two of the lateral part; almost all are surmounted by the architrave; they are made of limestone and were covered with a stucco which still coats them in several places…Stuart, who gave a description of the remains of this temple, had found fourteen upright columns during his journey. (36)

Cusani 1840

“Unici avanzi sono alcune colonne isolate nella parte piu alta della citta; (discussion of temple identification) e molti frammenti di cornici, capitelii e fregi adoperati invece di mattoni nelle nuove case, o dispersi fra i campi adjacenti.”

The only remains are some isolated columns in the highest part of the city; (discussion of temple identification) and many fragments of cornices, capitals and friezes used instead of bricks in the new houses, or scattered among the adjacent fields. (184)

Denison 1848

“We then mounted our horses and passed the seven celebrated columns supposed to have belonged to the temple of Minerva Chalamatis.” (141)

Hettner 1852

“They [the columns] show, moreover, evident traces of having been coated with stucco and colored red.” (134) Identifies it as Athena Chalinitis. (134)

Olin 1852

“A single temple of all the splendid structures which adorned ancient Corinth, the most opulent and luxurious town of Greece, now remains, or rather seven columns remain to show where a magnificent temple of Neptune once stood.” (143)

Howe 1853

Identifies it as the temple of Minerva Chalamatis. (35) “Of these [seven columns] three on the side and two adjoining on the front, still support their entablature; the architrave of both others is gone. They are limestone monoliths, near six feet in diameter at the base, heavy and ill-proportioned. This temple is supposed to have been erected in bc. 700, which may well account for its architectural defects. It stands in close proximity to the present village.” (35-36)

Baird 1855

“On our return to Corinth, we spent a short time in the examination of the only objects of interest that remain in thesite of a city which once exceeded Athens for commerce and population—a temple in the very midst of the modern village, and an amphitheater about three quarters of a mile east of it. The former is a hexastyle doric temple, of which only five columns belonging to the front and two on one of the sides are yet standing…” (158)

Burnouf 1856

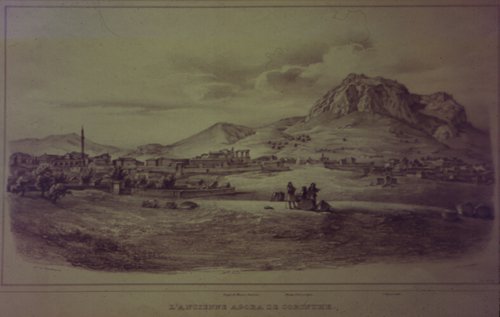

“Le temple est a l’occident de la ville moderne, un peu vers le sud, au pied de l’Acrocorinthe, dans une position assez elevee pour qu’on poisse le voir de loin. Il est etabli sur la roche tertiaire dont l’escarpement forme le premier gradin de la plaine.”

The temple is to the west of the modern city, a little to the south, at the foot of the Acrocorinth, in a position high enough to be seen from afar. It is established on the Tertiary rock whose escarpment forms the first step of the plain. (42)

7 columns, five with architrave, gives measurements. (42)

“...On y voit encore de grands morceaux du stuc jaune dont elles etaient revetues.”

You can still see large pieces of the yellow stucco with which they were covered. (42)

Taylor 1857

“We passed awhile before the seven ancient Doric columns of the temple of Neptune, of the Corinthian Jove or of Minerva Chalcidis or whatever else they may be.” (157)

“One of them [columns] has been violently split by the earthquake and a very slight impulse would throw it against its nearest fellow, probably to precipitate that in turn…” (158)

Wyse 1858

Identification of Athena Chalinits.

Pressense 1864

“De vieille Corinthe il ne reste que cinq colones dorique d’un style tres lourd et un amphitheatre romain. Un tremblement de terre, survenu il y a dix ans a jonche le sol de ruines plus moderne.”

Of old Corinth there are only five Doric columns of a very heavy style and a Roman amphitheater. An earthquake, which occurred ten years ago, littered the ground with more modern ruins. (316)

Jerningham 1870

Identifies temple as Athena Chalinitis. (86)

Belle 1875-1878

“Elles sont criblees de trous carres creuses par les Turcs pour y placer les poutres des masures qu’ils avaient appuyees contre les ruines…Cette colonnade, rongee a la base, briser, jetee hors d’aplomb par les tremblements de terre.”

They are riddled with square holes dug by the Turks to place there the beams of the hovels which they had leaned against the ruins... This colonnade, corroded at the base, broken, thrown out of plumb by the earthquakes.

Mahaffy 1876

“In the middle of the wretched straggling modern village there stand up seven enormous stone pillars of the Doric order…” (364)

Freeman 1877

“The columns stand over the modern village, over a site almost as desolate as that over which they must have stood in the hundred years between Mummius and Caesar. The other fragments, Greek and Roman, hardly come into view. But the lower city is not the true Corinth. It is the mountain citadel round which the great associations of the city gather.” (189)

Miller 1894-1898

“A few columns are all that is left.”