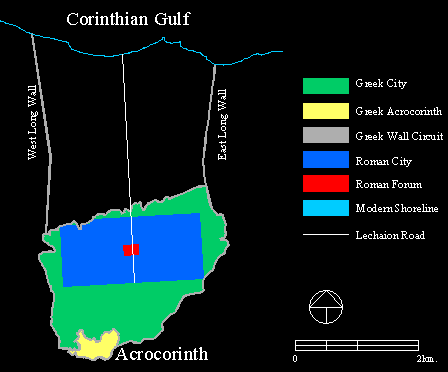

The ultimate price of Corinth’s leadership of the Achaean League in 146 B.C.E. in opposition to the Roman takeover of Greece was its destruction at the hands of the consul Lucius Mummius. According to Pausanias (7.16.8), the male citizens were killed and the women, children, and freed slaves were sold into slavery. The archaeological record seems to indicate that there was a partial and selective physical destruction of the buildings and structures of the city.

Evidence for a Roman Land Survey of Corinth

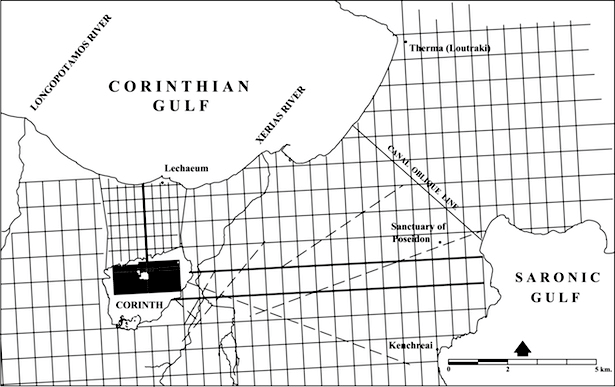

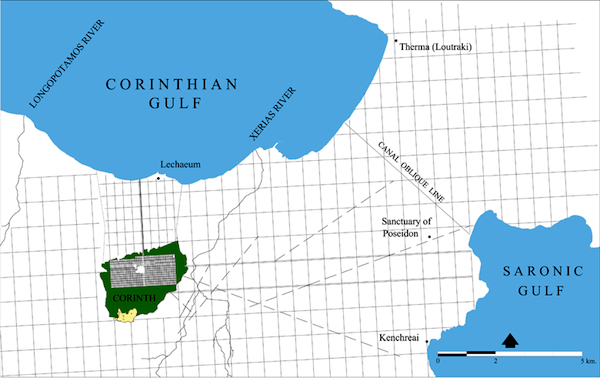

After the sack of Corinth, the Roman Senate sent ten commissioners to assist Mummius in the settlement of Greece and it is possible that a land survey of the Corinthia occurred at that time. Certainly detailed maps would have been made for the use of the commissioners and for planning the future use of the land; it is further understood that a major administrative reorganization took place. Pausanias implies that a special province, Achaea, was created, although it is more likely that the affairs of Greece were supervised by the governor of Macedonia. The Greek city was stripped of its civic and political identity and the combined literary and archaeological evidence suggests that it lost all semblance of an urban center from that time until 44 B.C.E. when the Caesarian colony was founded on the same site. Cicero mentions that people were living among the ruins during this period and that the confiscated land of Corinth was still vectigalis (taxable) as ager publicus (public land) in 63 B.C.E. Both Livy and Cicero suggest that Sikyon had taken over the care of part of the land of Corinth. Strabo says that the Sikyonians held most of the Corinthian land (chora).

We know from fragmentary elements of a Roman land law — the lex agraria, which is dated to 111 B.C.E. and was passed by the Assembly of Tribes of Rome — that parts of the ager publicus of Corinth, land acquired by the Romans in 146 B.C.E., were measured out for sale. This text is important because it may establish the date when at least a part of the land of the former Greek city of Corinth was formally divided up into Roman plots. It is not actually stipulated in the remaining fragments of the bronze inscription that a limitatio (boundary marking) was carried out at Corinth, and, therefore, scholars have considered the possibility that the Corinthian land was not centuriated at this time or, for that matter, at any time.

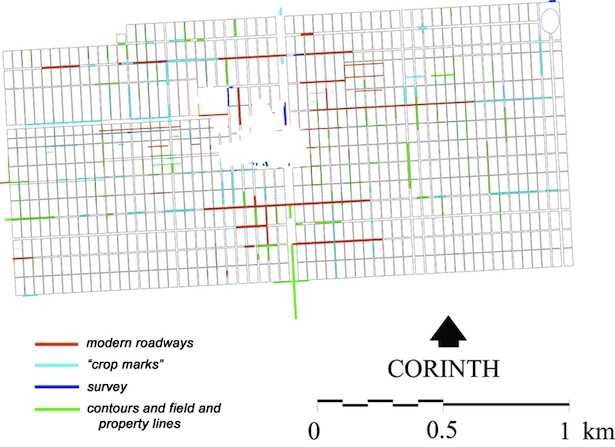

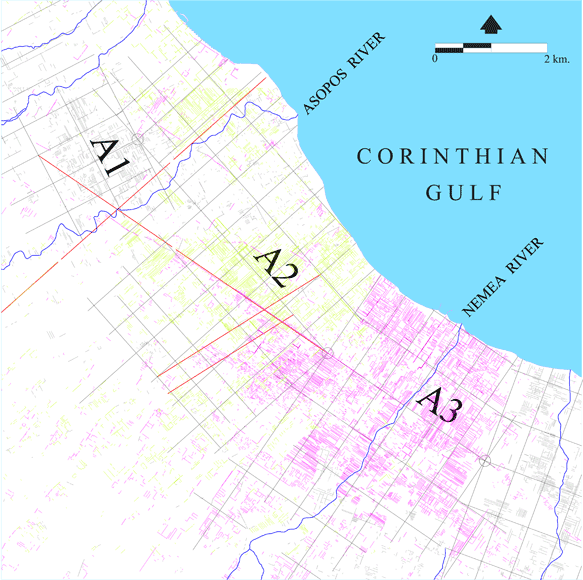

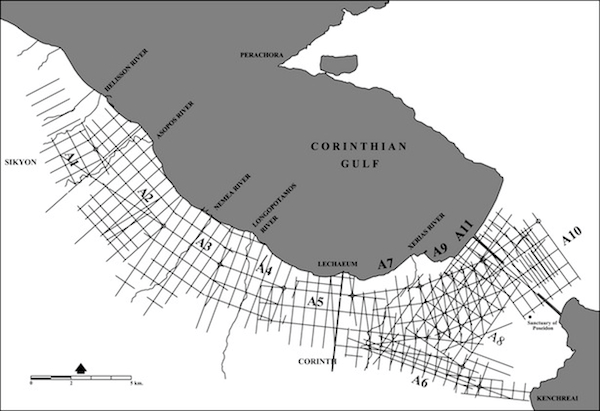

Some archaeological evidence exists to suggest that there was indeed a limitatio carried out during the interim period, probably related to the work referred to in the lex agraria. Archaeological evidence for this land division comes from a study of the Roman roads that may be associated with the period between 146 and 44 B.C.E., in the plain to the north of the former city. The evidence suggests that the framework for the organized grid of land to the north of the new city of 44 B.C.E. already existed after 111 B.C.E.

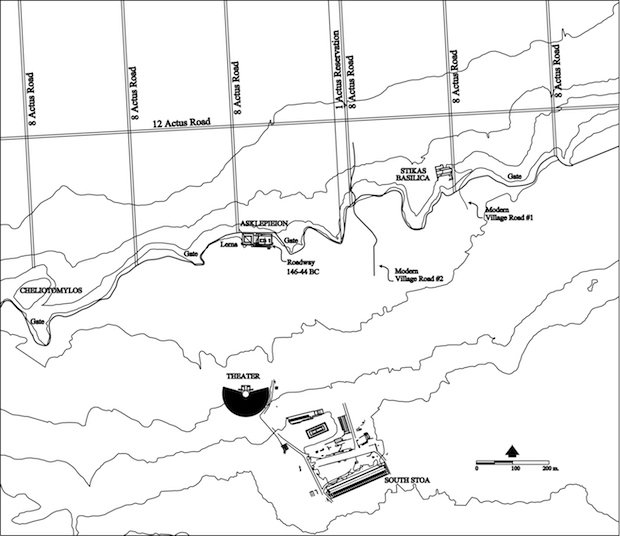

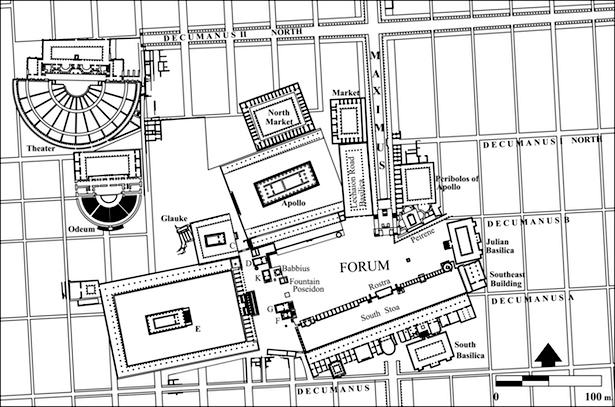

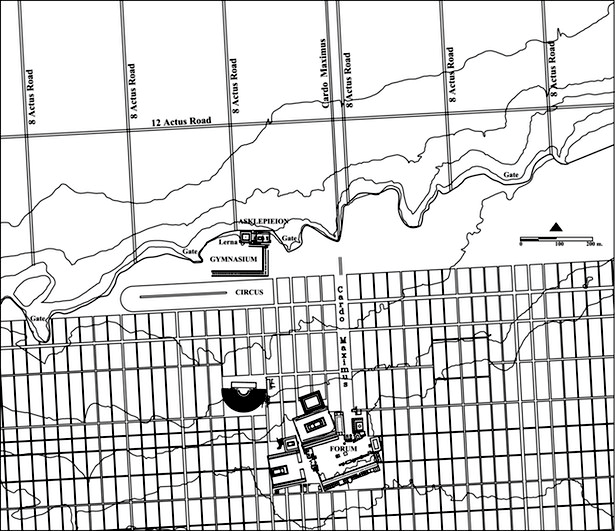

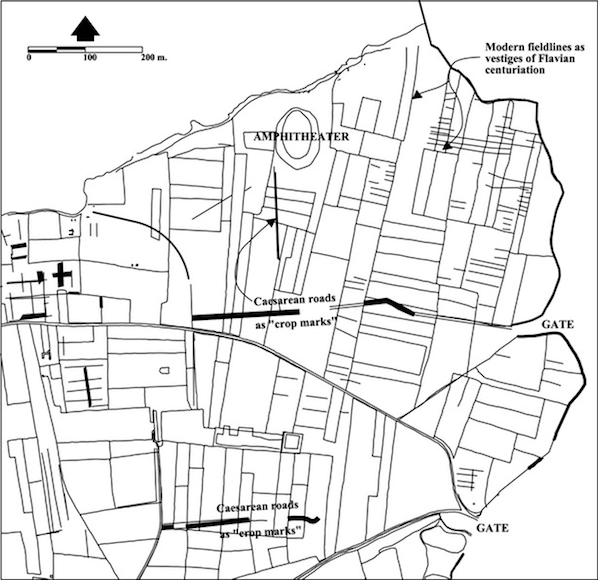

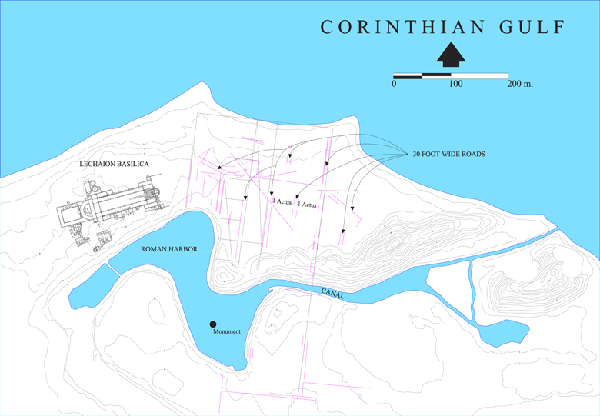

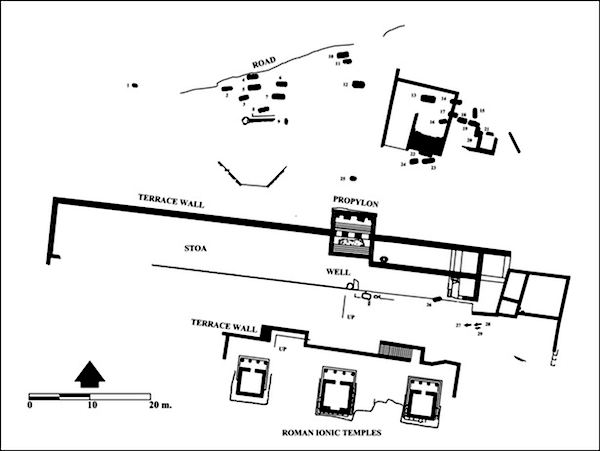

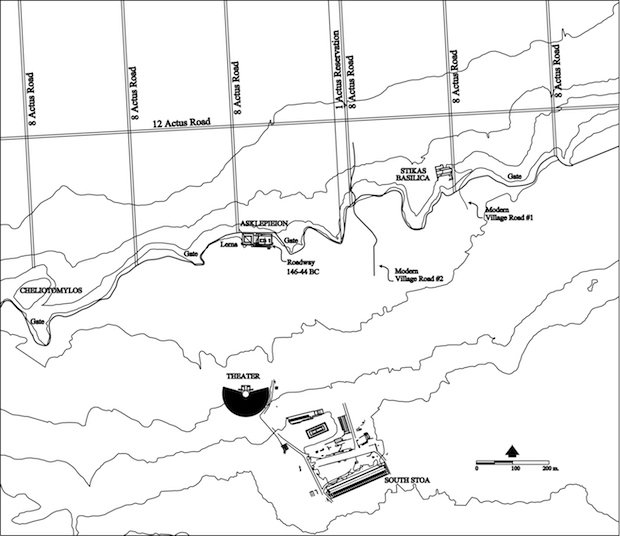

The attested archaeological evidence is found in the area of the Asklepieion, where the remains of a road for wheeled vehicles have been traced along the east-west ramp of the temenos. The wheel ruts of this roadway turn and point toward the northwest corner of the Lerna colonnade, where it is clear that the road passed down into the plain (Fig. 2). It appears that the northern Greek city wall was broken through in this place, in order to give the road a clear route for descent. It must be admitted that the route of the road has not been traced outside the city wall, although it clearly went there. Archaeological evidence indicated that the period of use of this roadway is between 146 and 44 B.C.E. The obvious question to ask is why the Romans wanted to have a roadway in this location at this time, since there were presumably several Greek roadways passing through nearby existing Greek gates in the circuit wall. The most plausible explanation is that the Romans, in following the lex agraria of 111 B.C.E., had divided the land to the north of the city in a formal limitatio. As a result of this, there would have been several new, important roadways going north-south that connected the former Greek city with the northern plain. Because the newly created Roman roads did not necessarily respect the location of the existing Greek gates, the walls would have been dismantled in places where the roads approached the city.

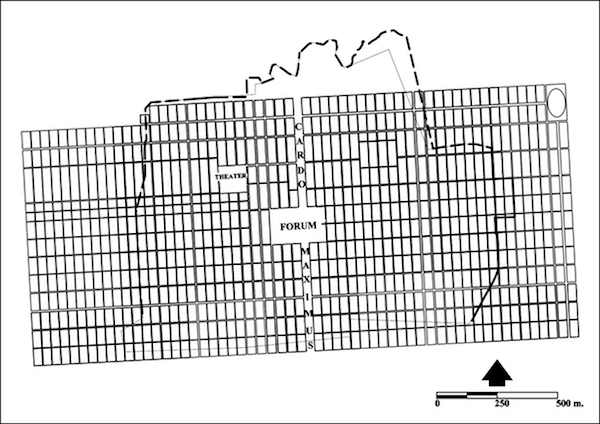

Figure 2. Greek Corinth, 146-44 B.C.E., with northern Greek circuit wall and interim period Roman land division to the north of the city. Portions of the two modern village roads are indicated. Contour lines are at intervals of 10 m. Corinth Computer Project.

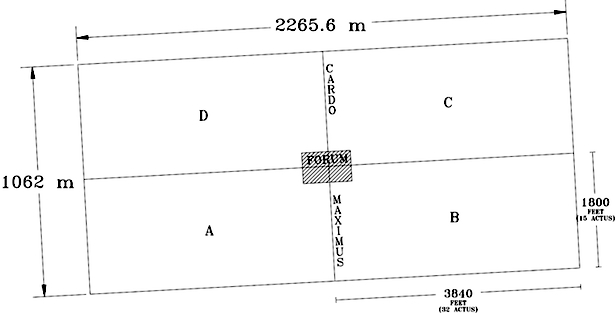

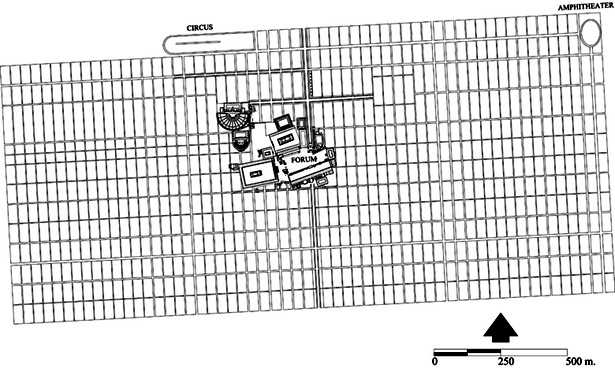

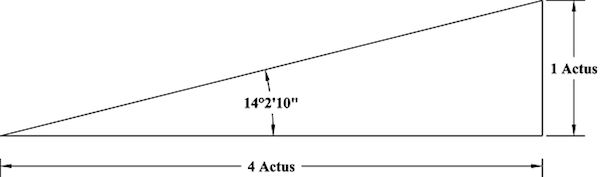

Evidence for land division into units of 16 × 24 actus (a linear measure of 120 Roman feet) at the orientation of 3° west of north is attested north of the city and is described below as a part of the discussion of the colony of 44 B.C.E. Evidence also exists for a sub-division of the 16 × 24 units into 8 × 12 units between the long walls, which would allow for a roadway where the Greek circuit wall has been broken through at Lerna. Since this road dates to the interim period, 146–44 B.C.E., can the other roads in the same system be dated similarly?

Furthermore, it appears that there was planned into this system of centuriation to the north of the former Greek city a reservation of one actus between the central 16-actus strips (Fig. 2), which suggests planning for an iter populo non debetur (“a public right of way does not exist over private land,” i.e. a public thoroughfare) 120 Roman feet wide. If this work was done in the year 111 B.C.E., then we may assume that the surveyors were already planning for the settlement of the former Greek city as a Roman colony, for it is possible that the reservation of one actus was included for a thoroughfare or for public buildings between city and port.

There is supplementary evidence for the organization of 146–44 B.C.E. in the existence of two modern roads that enter the village from the north and which are spaced at distances that suggest the organization cited above. Seventeen actus (2 × 8 actus units plus 1-actus reservation) to the east of the road at the Asklepieion is a farm road that leaves the plain and ascends the scarp towards the city plateau (Fig. 2, village road #1). This modern village roadway passes immediately to the east of the Early Christian basilica of Haghios Kodratos, dated to the 5th c. C.E. The basilica was built on the site of a Roman cemetery, and although its original date is not known, the road may be another feature of the land division of the 2nd c. B.C.E. Today a third roadway, probably another roadway of the same system, enters the city approximately midway between the two roads described above and at the 8-actus division of the Roman planning, (Fig. 2, village road #2). The association of village roads 1 and 2 with the 111 B.C.E. lex agraria is hypothetical without firm archaeological evidence. However, the location of the three roads with respect to each other suggests that the three may have been a product of the same project.

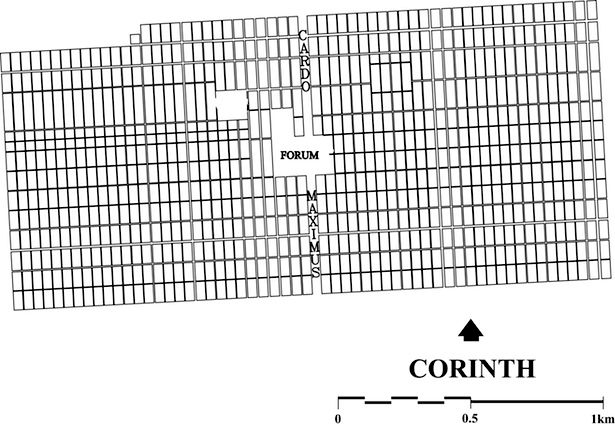

Although it is not clear at this time exactly how much of the Corinthia was included in the limitatio of 111 B.C.E., there probably was at least a regular and organized Roman division of land in the area immediately north of the former Greek city, and between the remains of the Greek long walls, where 16 × 24 actus units were subdivided into 8 × 12 actus units (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). In the present study this centuriation is documented as far west as the Longopotamos River, which may have been the border between Corinthian and Sikyonian land in the 2nd c. B.C.E. It is difficult to say how much of the rest of the Corinthia was centuriated at this time.

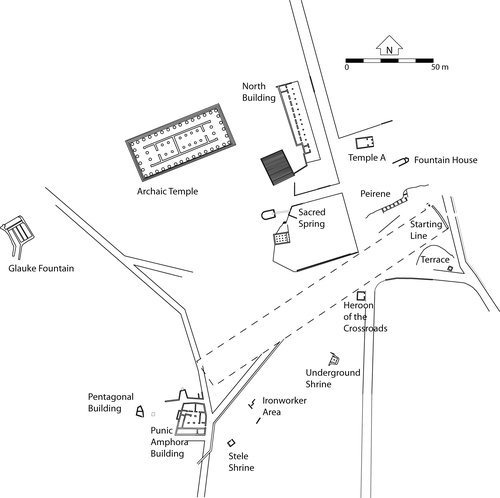

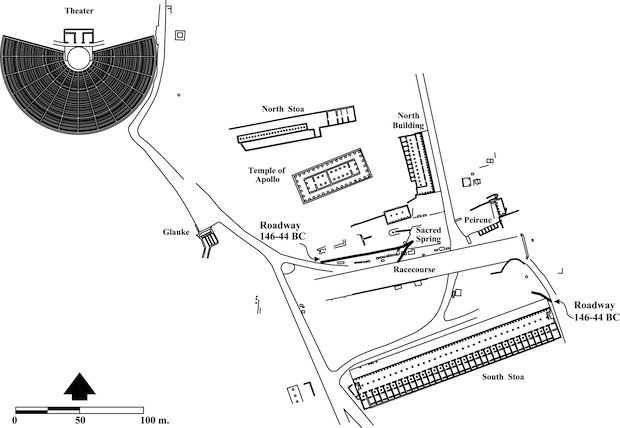

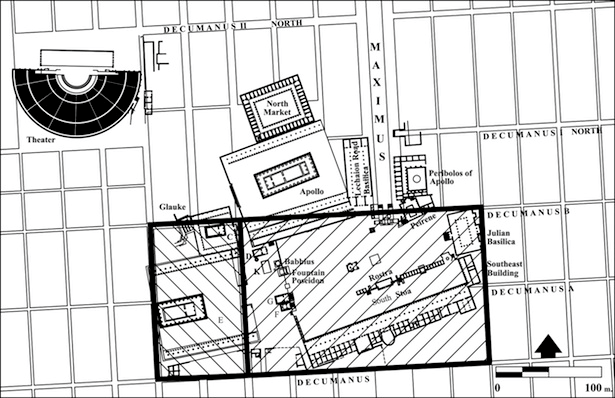

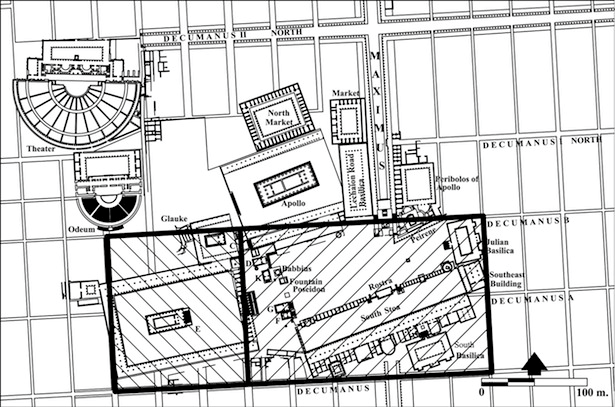

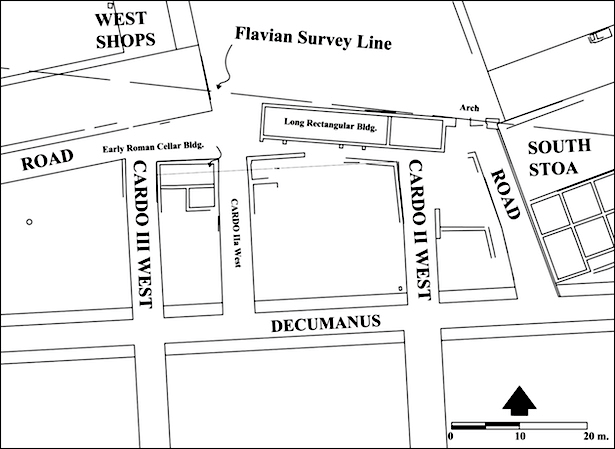

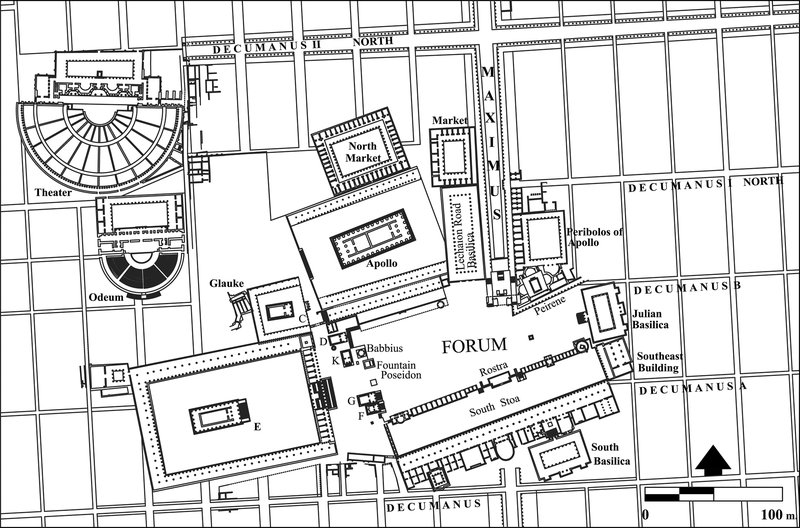

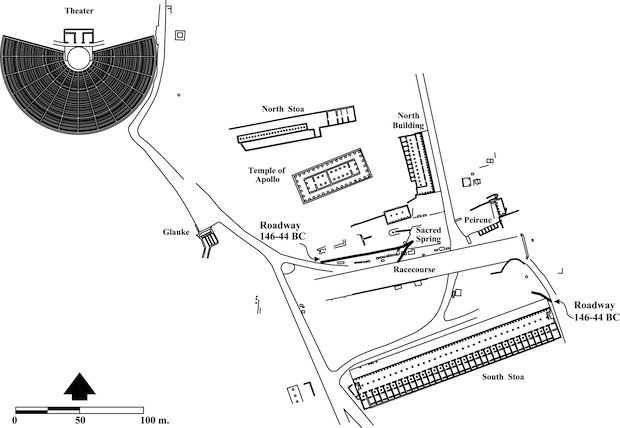

Figure 3. Greek Corinth, 146-44 B.C.E., illustrating the locations of the two east-west interim period roadways. Corinth Computer Project after Williams.

At least two other roadways dating to 146–44 B.C.E. exist near the center of the former Greek city. Wheel ruts going roughly east-west and crossing a low foundation at the northeast end of the South Stoa indicate that heavy-wheeled traffic used this route as a roadway (Fig. 3). That the roadway was abandoned shortly after the founding of the colony must, at least in part, be due to the fact that the construction of the Southeast Building closed off this corner of the forum. The roadway from the eastern end of the South Stoa has been traced across portions of the later Forum toward the west. Evidence for the second roadway datable to this period is found in the area of the temenos of the Sacred Spring. Deep wheel ruts (east-west) have been worn into the Greek triglyph terrace wall, ca. 15 m south of the Apsidal Building, and into bases of statues along the side of the abandoned sanctuary to the west of the triglyph wall (Fig. 3).

The combined evidence suggests that there was activity on the land and in the former city of the Corinthians before the time of the formal colonization in 44 B.C.E. It is assumed that the orientation and division of a limitatio of 111 B.C.E. was retained in the plain to the north of the city when the colony of 44 B.C.E. was founded.